Legend: Blue = Subjects connected with Judaism;

orange = dual rites, in different religions; brown = reference to

the bibliography.

“Matron Rabbis” or Rabbis?

Sara

Molho (2001-2005)

Translated to English (and partly rewritten) by author

(2008)

Feminization

of the Marrano-Religion in Belmonte

Jewish

Travelers Reflect Male-biased Preconditioning

Male-biased Preconditioning in Other Translations and in

Graphic Presentations

Itzhak Navon in Yigal

Losin’s Film

Feminization

Expressed in the Texts of Marrano-Prayers

She Who

Holds Both Talitot (Jewish prayer-shawls)[1]

Feminization of the Marrano-Religion in Belmonte

In

Under such circumstances a collapse of the Jewish communal-institutions occurred - no more synagogues, neither Rabbis, Khazanim (cantors), nor Religious Slaughterers among others, all male-oriented. In their past, men had to mingle with the Christian social-milieu more often than women, while making a living as peddlers in the neighbourhood. In order to protect their fathers/husbands/sons from the risk of being exposed as heretics, women were willing to discreetly take over religious functions. The probability of women being caught while preserving traditional rites and practices at home was lesser, but not nil.

Since none could possess any Jewish books such as the Hebrew Old Testament, the Aramaic Talmud, or any prayer books, these languages were totally forgotten! Therefore the obligation kept by Jewish males all over the world - of studying and interpreting the Holy Scriptures - could not be accomplished here, and gave way to other commandments housewives used to keep, such as educating the next generation, kashering-food, celebrating religious-feasts, keeping rites of purification etc. Women started to pray for the benefit of the whole family, in Portuguese, actually freeing male-members from this and other obligations (like some minor-fasts too). Centuries later, researchers called these aged ladies “khazaniot” (“female cantors”).

A feminization of religious-life imperceptibly emerged among the Belmonte Marranos.[2] Religious tradition was transmitted by heart from then on mainly from mother to daughter, contrary to Jewish conventions of transmitting in writing from father to son. Everybody started to revere the elderly sage-matrons, considering them as authorities concerning religious norms. In fact, I could trace this phenomenon in my own observations.

Since they also

lost touch with the Hebrew-calendar (including

the complex system of adding a 13th month seven times within

19 years), these sage-matrons did their best by assuming the

authority of determining the calendar and the dates of Jewish-feasts,

basically accepting the Christian-calendar, but “correcting” it according to

the moon. Therefore from time to time they used to discreetly roam together in

the fields, so as to have a good look at the appearance of the moon.

Also, women took over the religious-roles of the “rites de passage”, be it the clandestine marriage-ceremonies, or mourning and burial rites. Consequently elderly-women were called either Matron-Rabbis or Priestesses, according to the bias of those researchers who later discovered the phenomenon.[3] Sociologists, though, would prefer to treat them – according to their own biases of impartiality - as “opinion-leaders on religious matters”.

After being introduced to our normative Judaism throughout the 20th century, this roaming “Board of Sage-Matrons” or, on a smaller-scale, the female family-circle - still decided what should be done in religious matters. Inacio Steinhardt[4] cites Benvinda’s answer to his request at the end of the ‘80s:

– “With your

permission, madam, could we – Frédéric, the photographer and myself - attend your “Ceremony

of the Marror” (bitter-herbs)

at your place? Is it all right?

– I do not know,

sir. I shall consent to whatever you decide with my daughters and my

daughters-in-law. Once we did not let in anybody except family-members. But

by now you are family, are you not?”

Collecting Research Data

Gathering social-findings while living within

a group of people is multifaceted. Apart

from my own (anthropological) participant observations and

personal experiences during the years 1994-2000 and on, I relied on data

supplied by informants, whom I consider as a very reliable source

of information. It is understandable why I consulted on matters concerning the

Marrano-tradition[5]

mostly women, my black-aproned sisters,

and to a lesser degree men. Some of the women were young,

but 3-4 others were elderly. All were kind enough to answer my probing

questions, or share with me their own experiences, especially as to these

topics:

1. The Marrano-past, after historical

circumstances unknowingly widened the gap between their (Marrano) tradition and

mainstream normative–Judaism;

2. Their personal opinion on the

multi-stage process of conversion to normative,

Halakhic-Judaism in Belmonte, a very slow

process marked by fluctuations;

3. Their personal experience before

and after their personal return to Judaism in the first half of the ‘90s.

Apart from women who did not convert to Judaism, most women I interviewed – both young and old – were respectable within the newly-converted group, and manifested devotion to their new normative-Judaism. The middle-aged Isabel Morão Rodrigo[6], always accompanied by her elderly mother, relies on her while relating the stories about the Marrano-past, e.g.: about marriage in Church, after the covert-marriage at home: “Isn’t it so, my Mother? Am I not right?” She would turn to her for confirmation.

With the assertive Aurora da Costa Diogo

I chatted a lot, asking questions about the Marrano-rites, often learning a lot

from her, for instance: about the cleansing-rites on the (X2) 40

days-of-purification preceding either Yom-Kippur (Day

of Atonement) or Passover. The Israeli Rabbi S.S. and his wife, too, might investigate or

consult her in my presence, seeking sometimes for her help. Her authoritative

tone might stem from the fact that her late mother, born in the nearby town of

Covilhã, was considered as an energetic Matron-Rabbi [7],

whose influence spread beyond the boundaries of her nuclear-family,

encompassing all the Marranos in Belmonte. As a matter of fact, she moulded

their religious norms.

Jewish Travelers Reflect Male-biased Preconditioning

Benjamin

Minz’s Book

As mentioned, Aurora da Costa’s mother was revered by Marrano circles far beyond her own nuclear-family.[8] We can learn about it even from Jewish travelers’ literature. Her religious authority used to be so obvious that the learned Yiddish-journalist Benjamin Minz, writing about his visit to Belmonte in the early ‘30s, erroneously concluded that rather… her husband “is the Rabbi of the community”, as he labelled him.[9] However, it should be stressed that even after Samuel Schwarz’s appearance in Belmonte (1917) religious-authority continued to be held by the Matron-Rabbis! My own findings indicate that even after conversion to Judaism in the ‘90s, husbands/sons/grandsons went on seeking the guidance of their wives, mothers, grandmothers or mothers-in-law (especially if they were senior, but sometimes even if not). No doubt it even occurred among families whose male members were personally involved in the (male) creation of the new Community-Council. Such deeply imprinted practices - lasting for about 500 years - cannot be uprooted at once!

It seems that we – belonging to whatever section of normative-Judaism - cannot easily accept the fact that women constitute the religious-authority in the Marrano-ambience. Because of our male-biased preconditioning, typical of mainstream-Judaism, some of us – not only Benjamin Minz – ignore/misunderstand/forget the notion that religious-roles are feminized in Belmonte. Those of us who are sometimes mistaken include even such important researchers as Nahum Slouschz or Itzhak Navon, let alone those of lesser importance, like myself and my generation.

Nahum Slouschz’s Book

Thanks to the

same male-biased preconditioning, when Nahum Slouschz translated into Hebrew

the Marrano-prayers which he added to his book (1932) - in fact, most of them

borrowed from Schwarz’s (1926) book in

Portuguese - he applied the masculine-gender in Hebrew. That is not

so! Most prayers were uttered (in Portuguese) by women,

the Matron-Cantors, not by men - therefore the verbs

should be conjugated either neutrally or clearly in the feminine-gender![10]

Even though Slouschz studied and wrote about feminization of religious-roles, on p. 141 he treats the person praying as masculine. On the same page, dealing with the Benediction

for the

New Moon, he remarks that it seems this benediction (only?) had

been created by a woman, since in his translation he refers to the

person praying as: “God’s devoted maidservant”. Again, on page 170 he

deals with women’s crucial role in the clandestine Marrano

betrothal-ceremonies - in the masculine gender. In another prayer Slouschz translates from Schwarz’s appendix,

he calls this hymn “a

women’s hymn” (again: only this one?). According to him it might allude to the last chapter, in Psalms 150.[11]

÷åîå, éìãåú, äùëéîå,

ëáø äàéø

äùçø,

ðäìì ìàì

òìéåï,

äåà éçæ÷

øåçðå.

äììåéä á÷åì

ðáì,

ùëåìå àåîø

ëáåã,

äììåéä, éìãåú,

äììåäå

á÷åìåú ã÷éí,

äììåéä, áúåìåú

äììåäå

á÷åìåú òøáéí,

äììåéä, ðùåàåú,

äììåäå

á÷åìåú öìåìéí,

äììåéä àìîðåú

äììåéä

á÷åìåú èäåøéí,

ìàãåï ëì

äàäáåú

äììå éìãåú

åôøçéí!

This is Schwarz’s original Portuguese hymn, along with its

English translation:[12]

|

Levantai-vos meninas cedo |

Get up early young girls |

|

Já quere amanecer, |

Dawn is aproaching, |

|

Louvaremos ao Altisimo Senhor, |

Let us praise the Most High God, |

|

Que nos ha de fortalecer. |

Who would strengthen us. |

|

Louvai o ao som da viola |

Halleluia to the sound of viola |

|

Ele é tudo som e tudo gloria. |

He is all sound and all glory. |

|

Louvai o Senhor meninas |

Halleluiah young girls |

|

Louvai-o com vozes finas, |

Halleluiah with fine voices, |

|

Louvai o Senhor donzeias |

Halleluiah maidens |

|

Louvai-o com vozes belas |

Halleluiah with pretty voices |

|

Louvai o Senhor casadas |

Halleluiah married women |

|

Louvai-o com vozes claras |

Haleluiah with clear voices |

|

Louvai o Senhor viuvas |

Halleluiah widows[13] |

|

Louvai-o com vozes puras |

Halleluiah with pure voices |

|

O Senhor de todos os amores |

The Lord of all the loves |

|

Louvai

meninas e |

Halleluiah young girls and flowers. |

Psalms 150 is not a feminine

hymn, it is general.

Therefore it is surprising that Slouschz

does not wonder why the parallel masculine age-groups and/or personal-status are altogether missing in

this Belmonte-hymn. I presume they were

dropped since in Belmonte almost all prayers were chanted by

women of all age-groups and/or personal-status. In the Marrano-ambience it was the women’s duty to chant “Halleluiah”, instead of men and for them, too!

Male-Biased Preconditioning in Other

Translations and in Graphic Presentations

Minz or Slouschz are

not to be blamed. I myself slipped into the same pitfall of the male-precondition! In the first drafts of my translation to Hebrew of

“A Prayer to My Guardian Angel”, cited in A. Canelo’s booklet[14], I too

automatically applied the masculine conjugation instead of the neutral

Portuguese first person. All of us are preconditioned! It took me some time to

realize my own mistake and correct it.

Supposedly, also

the translator (into Hebrew) of Brenner et al’s

documentary film Les Derniers Marranes,[15] about

Passover among the Marranos - acted according to my own precondition as

well, (or maybe he translated the written

text without comparing it to the photographs themselves?). Regarding the

film, one obviously notes that it is a housewife, dressed in white, who

is chanting the prayer while kneading dough preparing the Matzah (unleavened-bread), though the Hebrew-text

written beneath it is erroneously again in the masculine gender.

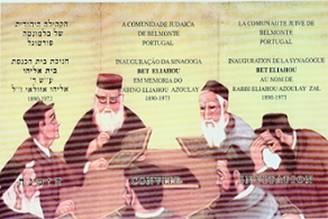

Another comparable example is the graphic illustration on the

invitation to the inauguration of the new synagogue

in Belmonte at the end of 1996. It is not

important whether the artist was gentile

or Jewish, since either way he surely used stereotypes describing normative-Judaism – not Marrano - as demonstrated

here:

Trilingual invitation to

the inauguration of the Belmonte synagogue,

on the 500th anniversary of the publication of the Decree of

Expulsion

of the Jews from

One could spot visual elements that could have never occurred in Belmonte in the last 500 years! Namely: A gathering of Jewish men arround a table in order to study the Holy Scriptures. They wear particularly Jewish hats (some of them typical of Sephardi religious-sages, others probably Ashkenazi). But all these Jewish symbols have nothing to do with daily life in secretive Belmonte. After the publication of the Decree of Expulsion (1496) and its application (1497), Marranos could not congregate overtly in safety anywhere in town. The word synagogue (Greek) is originally composed of two Hebrew words: “Beit-Knesset”, literally signifying a house of assembly. As a matter of fact, the only safe places Marranos could assemble peacefully were… the noisy, colourful, crowded marketplaces.[16]

Please note: I do not

criticize neither the artist, nor the one who ordered his graphic-work!

God forbid! It only goes to show that their notions belong to mainstream-Judaism, rather

than to the divergence

of Marranism. These stereotypes could not exist in

Itzhak Navon in Yigal Losin’s film

In Y. Losin’s (1992) documentary film,[17] one sees Mr. Itzhak

Navon, former 5th President of Israel,

standing among a group of Belmonte Marranos. At that time they were not yet

converted to Judaism; conversions would start

only 2-3 years later. One gets the impression that he desires to hear a

Marrano-prayer. Although Navon accumulated a

lot of knowledge on the subject before arriving, he turns instinctively

(precondition!) to a man, wishing he would recite the prayer. But - being

a male - the perplexed

person is not sure he could fulfill the honourable visitor’s request: knowing

prayers was never a male prerogative in Belmonte for the last 500 years!

Therefore he looks around - maybe a woman might approach and save him,

while he starts murmuring in hesitation a refrain

connected to Navon’s request: “Adonaio,

Adonaio”… Calling God by name is the introductory refrain to the

Marrano-parallel in Portuguese of the biblical Song on

Crossing the Red-Sea[18],

covertly sung in Belmonte on the eve of the Marrano-Passover. Alas, God alone

knows whether this poor man remembers how to go on chanting… On a

normative Yom-Kippur in the early ‘60s, a few

Belmonte Marranos appeared at

“We do fulfill religious-commandments.

But it is women’s obligation to know the laws and preserve

our mothers’ religion.” Thus they

referred all those asking probing questions - too difficult to be answered by men

- to their wives, who gathered upstairs, in the synagogue’s women’s gallery.”[19]

Feminization Expressed in the Texts of Marrano-Prayers

I described above how historical circumstances compelled women to fulfill male important religious-roles. It resulted in a unique prestigious-status of women within the family. Could ancient Marrano-prayers reflect similar attitudes traceable even today?

One example is found in a Marrano blessing. It seems that the morning female Halakhic prayer, saying: “Blessed be He for having made me according to His will” (in contrast to the derogative male equivalent: “Blessed be He… for not having made me a woman”), inspired the female Marrano Blessing for Hand Washing, but here she is not degraded at all:[20]

“The angels praise God who created me and

gave me a good life, who granted me water to wash, a towel to dry with, eyes to

see, hands to gesticulate, ears to hear, and has made me a woman...”

Given their duty to pass on

their tradition to the forthcoming generations from mother to

daughter, it seems appropriate, if not necessary, to implore God to protect

women in particular. This is reflected in the Marrano Grand-Prayer for Yom-Kippur, based on a normative one (although women

prayed, again Slouschz

erroneously uses the masculine

gender at the beginning not cited here):

“…May Thou take my daughters into Thy holy and

divine consideration, o Lord, and grant them a blessed-lot, so they would be

able to comprehend Thy holy and divine Law, and to serve and praise Thou;

better trust the Lord than any human dignitaries…[21]

She Who Holds Both Talitot (Jewish

prayer shawls)[22]

At the end of the ‘80s, about 6-8

Marrano young men started the process of return

to the male-oriented normative Judaism.

However, they would not have done anything before seeking the permission, and

assuring the support, of their mothers and wives in advance, as

some of them told me afterwards. As to these Matron-Rabbis, they did not

put up any obstacles, and willingly consented to give up their prestigious

role, without evoking any leadership-struggle or personal-crisis. Actually,

they always considered their role as a temporary one, which should be given back

whenever possible.

After the 1992-93 formal return, wives were sometimes compelled to

remind their husbands it is time to go to synagogue

to pray, since men were not yet accustomed to fulfill newly-acquired

duties as praying, let alone the gathering of a Minyan

(a quorum of 10 males needed for praying) at the synagogue.

Unconverted

Marrano women preparing the “sacred-wicks “

together with their converted to normative-Judaism relatives, 1994

One should not ignore the actual double practicing of rites, though very different

from the past one. Then the overt Christian religious-rites competed with

the covert Marrano tradition; but my observations - shortly after the return - revealed rather a dissimilar double-practice: that of the covert Marrano

ramification versus the overt mainstream-Judaism.[23]

One example is of mourning-rites in the case of a deceased person in 1997. The double mourning-rites held at his home included on

one hand the male Minyan-reunions[24],

and on the other - at different times and in a somewhat covert manner - the female

Marrano mourners’ reunions[25],

which included also several newly-converted ladies, along with their unconverted

relatives.

Another

example is that of Marranos who did not return to

Judaism, but despite it, they used to

celebrate meticulously their own Marrano Kippur

or Passover according to the Hebrew calendar. Some of these women (more

often than men, since they are considered responsible for the well-being

of their families!) even tend to approach the synagogue

and participate in normative-rites as much as

they can! It did occur several times in my presence around 2000 and on. This

fact still places women in their high prestigious status as ever.

According to

both examples, women are apparently still “holding

both Talitot” - that of the Marrano-past together with the contemporary Halakhic “new” religion. This applies to those who

did convert to Judaism as well as to the

unconverted women. Many other examples pointing to the same conclusions

are unfolded elsewhere on this site. Nevertheless, it

must be stressed that this type of performing

double sets of religious rites (Marrano

versus Halakhic, both

“Jewish” in their eyes) is altogether rather scarce. Many observers

assume it is temporary and might soon vanish for ever.

An attire similar to that of the

Elderly Matron-Rabbis

© All rights reserved to Sara Molho, 2001-2008

Publication of

this article is permitted, but without changes,

and with full

mention of the source: