Legend:

Text in blue =Subject connected with Judaism,

orange = Dual rites, in different religions, brown =

Bibliographical reference

from:

Feathers, angels, scales - sacred matters,

chapters

1-6: Sociological research [1994-2000 & on]

on Marrano-descendants in Belmonte, along with personal impressions [1994-2007]

of the researcher

Sara Molho (2001)

1. Rainbows

2. Angels

3. “Ave de Pena”

4. Marrano Kippur and

Passover

2.

Angels

Translated

from Hebrew by

Mark Elliott Shapiro (2007)

For the past 500 years and up to this

very day, even after most of them have converted to Judaism, the atmosphere

among the descendants of the Marranos, or crypto-Jews, in Belmonte is such that

they still anticipate the occurrence of a miracle at every moment. Their daily

routine assumes the constant presence of a whole flock of angels who, in their

view, have been sent by God to watch and protect them, in most cases because

the Marranos themselves have requested their presence.

According to the Marranos, their custom

not to emerge from their homes on Yom Kippur,

the Day of Atonement (since a synagogue is not

part of the Marrano way of life, the home becomes the sole place where true

communion with God can be achieved) stems from the fear that they might weary

their “guardian angel” in their sallies on such a holy day.[1] Thus, in

the first years following their conversion, they would remain in the synagogue

on Yom Kippur, or Dia Kipure in

their language, for the entire day (see below Noite Kipura); they even tried to impose on me this prohibition on

going outside. They cite this heavenly presence and its great sensitivity as

the reasons for their extreme reluctance at having strangers join them in their

ceremonies. They fear that strangers could confuse the descending angels or

even prevent the Marrano matrons from correctly performing their

ceremonies, which require total concentration on the part of both the

worshipers and the invisible entities who respond to their calls. This is the

explanation I was given concerning the secrecy surrounding their hanuccat habayit (house-warming) ceremony, for

example. Apparently, this explanation is what lay behind their initial

rejection in the late 1980s of Frederic Brenner's

request to film the Marrano ceremony of baking matzot (unleavened bread

eaten on Passover). Only after they were explicitly promised that the filming

would stop immediately if the matron felt that “she was forced to ask us

to leave” and only after they were promised that “we would not be angry” if and

when leaving the room, did they change their mind and agree to the filming.[2]

The Marranos thus customarily turn to

the “upper worlds” at every possible moment, in their daily prayers, or in the

special prayers composed for any difficulty or distressful situation they might

encounter. They do so – either directly addressing God

or appealing to his messengers, the various angels

– and sometimes, when appealing directly to such mediators, they use the second

person plural (an element that can

rarely be found in normative, rabbinic or halakhic, Judaism, where, if they are

referred to at all, the angels are spoken of in third person plural).

Nearly every event in their lives – such as, for instance, the tolling of a

church clock or the rumble of thunder – is “covered” by a special prayer. In

these two instances, the appeal is made directly to God.[3]

I know for a fact that, although they were documented in the past from oral

testimony by Marranos, some of the prayers that address a specific event have

not yet been published, because of the respect researchers like David Canelo

felt for the value that their research subjects (who were also their friends)

so deeply cherished – namely, secrecy.

Sometimes, the Marranos turn to the

angels, directly and in second person plural, addressing angels in

general:

“Anjos

benditos, profetas, patriarcas, monarcas deante do Senhor...”

“May you, most welcome angels,

prophets, patriarchs, and kings serve the Lord.[4]”

However, frequently, they will address

their private angel, namely, their guardian angel:

"Anjo da minha guarda

não te apartes de mim.

O Senhor te dê bons dias

e tu anjo mos daras a mim.

Anjo da

minha guarda,

anjo bem

aventurado,

te peco e

rogo,

que o Senhor

me livre do pecado.”

“My guardian angel,

Please do not abandon

me.

May God grant you good

days

And may you, o angel,

convey them to me.

My guardian angel,

O angel whose lot has

been blessed,

I ask you, I beseech

you,

May God deliver me from

sin.”[5]

Or:

"Anjo

da minha guarda,

anjo, estas tu por ai?

O Senhor te dê boas tardes

e tu anjo das-mas a mim.

Anjos que o Senhor me deu

para a minha

guia

e para a

minha companhia…”

“My guardian angel,

O angel, are you there?

May God grant you good

evenings,

And may you, o angel,

convey them to me.

O angel, whom God has

granted me

To guide me

And to serve as my

companion....”[6]

Sometimes, the appeal is made to “celebrity-angels,”

whose fame and special functions are praised by everyone, such as the holy Angel

Raphael, a much beloved angel among the Marranos, who became aware of his

unique talents through the apocryphal Tobit, or Book of Tobias:

“Anjo S.

Rafael bendito, que assistes ao meo Senhor,

peco-te anjo

bendito, sendo omeo advogado,

faze-me esse

favor, sendo o meo amparo fiel,

para pedires e rogares ao grande Deus de Israel,

que me

guarde a mim e todas as minhas pressas e nececssidades…”

“Holy, blessed Angel

Raphael, you who stand before God,

I beseech[7]

you, o blessed angel, be my advocate,

Give me a good omen,

and be my faithful shield,

So that you may beseech

from and implore the great God of Israel

To guard me and my

person and see to all my day-to-day needs....”[8]

In the eyes of the descendants of the

crypto-Jews of Belmonte, anticipating the appearance of the seraphim and

cherubim that populate their beautiful prayers - is completely realistic,

and their existence is an unquestionable fact. Their conversion in the early

1990s did not change this attitude.[9] In any case,

I myself heard with my own ears the phrase “seraphim and cherubim” in

the secret prayers to which I was made privy by the elderly Marrano matrons

who had not converted to Judaism. This happened in the home of Maria-Fernanda

Rodrigo, during the preparation of the “holy, blessed wicks” for the memorial

candles lit on the eve of Yom Kippur ( just

before “Noite Kipura” in their language). A similar, but by no means identical,

prayer has been documented by Schwarz:

“…Anjos, archanjos, serafis, cherubins,

patriarchas, monarchas…”

“…O angels, ministering angels, cherubim,

patriarchs, kings....”[10]

This was not the prayer

that I heard while the wicks were being prepared. However, in all the prayers that

various scholars have heard at various times from the mouths of matrons,

there is always a hierarchy of celestial and earthly entities.

The clandestine, lengthy domestic

ceremony I witnessed with the Rabino's wife in

Maria-Fernanda's home on two occasions – in

1994 and 1995 respectively – was also attended by her sister Anna and

her nieces, all of whom are Marranos who have not converted to Judaism, as well

as by Maria-Fernanda's daughter, Beilinha, with whom we are already acquainted

(in chapter 1). Although Beilinha had converted, she came to help her mother

prepare the sanctified wicks, in accordance with Marrano tradition. The

ceremony is performed only by women; in the course of the ceremony, the men

(except for the very elderly or the ill) were supposed to protect us by

standing guard outside.

-

You can show these photographs (there are many such illustrative

photographs in this and other chapters – S.M.), if you wish, but only in

This ceremony of preparing the wicks precedes

by several days the holy day of Yom Kippur,[11]

although each family holds it at a different time. The most important of these

prayers is recited 73 times for each wick, and the number of wicks

corresponds to the number of family members – those who are still living and

the deceased who should be memorialized. The reason for the lengthiness of the

ceremony is this abundance of prayers. There are also brief prayers each of

which is customarily recited three, five or seven times.[12] When

repeating the short prayers each of which they traditionally recite three to

seven times, the women would bend their fingers in the counting process. A

different method is employed when the prayer is recited the maximum number of

times, that is, 73. For that level of counting, preliminary preparations

are required and they entail the placing of two small bowls on the table. One

of them contains a large amount of chickpeas, each of which is noisily dropped

into the second bowl each time the prayer is recited, for a total of 73

times. The Marrano women explain that 73

is the number of God's names, as is stated in

their prayers. However, in normative Judaism, the accepted number of God's

names is 72.[13]

|

|

|

|

Counting

process where fingers are used, 1995 |

Counting

process where chickpeas are used, 1994 |

In the same prayer that the women

customarily recited the maximum number of times, that is 73, the seraphim

and cherubim were included in the opening text, in a hierarchy descending

from God himself, only a very few of whose names – including Adonai – were mentioned, the only Hebrew

word that clearly survived among the Marranos. As both the Rabino’s wife and I recalled, immediately after the reference

to God himself, there was a reference to the Angel Raphael, whose full

name was mentioned, followed by the reference to the cherubim and seraphim. From

the various levels of angels to the various levels of mortals: further down in

this hierarchy were the prophets, who headed the list of the mortals

(and were not excluded this time). Following them, in descending order,

were the other mortals: patriarchs, kings, etc.

Unfortunately, while listening to the

prayers, I was unable to write them down. As noted above, in an unusual

gesture, I had been given permission to take pictures of the two ceremonies,

and, content to do that and no more, I did not want to make things any harder

for the Marranos, who were troubled to the point of despair by the presence of

strangers who interfered with the Marranos' flock of angels, and perhaps with

another flock of transparent “tiny souls” in whose existence they believed.[14]

|

|

|

|

Different

stages in the ceremony of |

|

A few days after the ceremony in 1995,

the Rabino, his wife and I tried, together with

Beilinha, to reconstruct the prayers each of which was recited the maximum

number of times (73). These are the prayers that she recited yearly throughout her

life in her mother's home. However, in comparison with what the Rabino's wife and I had heard repeatedly in 1994 and

1995, and despite her willingness to help, the memory of Maria-Fernanda's

daughter – who herself was, as noted above, a middle-aged woman – proved very

faulty. What she recalled and what her husband Ricardo recorded in writing

before our eyes (see below) did not reflect what we had both

heard with our own ears! For his part, the husband was unable to help us in the

reconstruction work, because, of course, his function had always been to

protect the women worshipers by being on guard outside. In 1994, he did

so as he sat, with such seeming innocence, in the coffee shop located on the

ground floor, while, in 1995, he did so from his factory and by means of a

cellular phone, an innovation that had just reached Belmonte. The failed

attempt to reconstruct this beautiful, moving prayer immediately brought home

to me both the problems involved in the transfer of a purely oral tradition and

the important function of recitations conducted over and over so many

times. The much-repeated recitations are intended to ensure that the daughters

will remember over the years the text of the long and/or particularly important

prayers recited in their mother's home. The number of repeated recitations for

the shorter prayers could, of course, be smaller without any fear that the

daughters' memory might betray them.

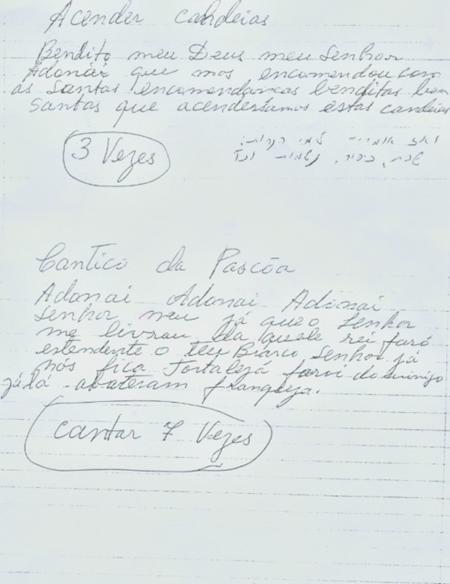

Document:

The (relatively unsuccessful) attempt to reconstruct, in

Ricardo

Vaz-Nunes’ handwriting, the prayer recited by his wife Beilinha

In light of all the above, I felt as if

sometimes dozens of angels were clustered around me, as I walked through the streets

of the Judaria; they were transparent, of course, but they certainly existed.

Let us assume that the guardian angels of my friends were very near to

my person, so much so that I sometimes feared that I would step on their toes

by accident. It is thus not surprising that, in this Marrano atmosphere, I

could imagine that, in their ardent desire to respond to any urgent request

from Belmonte, the angels did not require any Jacob's Ladder or any other

biblical/heavenly means of transportation; they could simply slide down from

the heavens straight into our world riding atop ... the colors of the rainbow,

just like the trained firefighters (bombeiros), whose presence is so prominent,

and so audible, in rural regions like Belmonte (if in Portugal the firefighters

slide down the fire-station poles, as in American films.) What is certain is

that rainbows are readily available in Belmonte's skies. In any event, it seems

to me that their frequency and the confidence that they will appear sometimes

exceeds the expectations regarding the arrival of the rural buses that travel

between the various villages and which we, mortals who have not yet learned how

to fly, require in order to get around. And we can all be grateful that the bus

service has recently improved considerably.

|

|

|

In

the past, it was customary |

© All rights reserved to Sara Molho,

2001

Publication of this

article is permitted, but without changes,

and with the stipulation that full mention is made of the source: